from http://www.shutterstock.com

Warren Midgley, University of Southern Queensland

It’s often thought that it is better to start learning a second language at a young age. But research shows that this is not necessarily true. In fact, the best age to start learning a second language can vary significantly, depending on how the language is being learned. ![]()

The belief that younger children are better language learners is based on the observation that children learn to speak their first language with remarkable skill at a very early age.

Before they can add two small numbers or tie their own shoelaces, most children develop a fluency in their first language that is the envy of adult language learners.

Why younger may not always be better

Two theories from the 1960s continue to have a significant influence on how we explain this phenomenon.

The theory of “universal grammar” proposes that children are born with an instinctive knowledge of the language rules common to all humans. Upon exposure to a specific language, such as English or Arabic, children simply fill in the details around those rules, making the process of learning a language fast and effective.

The other theory, known as the “critical period hypothesis”, posits that at around the age of puberty most of us lose access to the mechanism that made us such effective language learners as children. These theories have been contested, but nevertheless they continue to be influential.

Despite what these theories would suggest, however, research into language learning outcomes demonstrates that younger may not always be better.

In some language learning and teaching contexts, older learners can be more successful than younger children. It all depends on how the language is being learned.

Language immersion environment best for young children

Living, learning and playing in a second language environment on a regular basis is an ideal learning context for young children. Research clearly shows that young children are able to become fluent in more than one language at the same time, provided there is sufficient engagement with rich input in each language. In this context, it is better to start as young as possible.

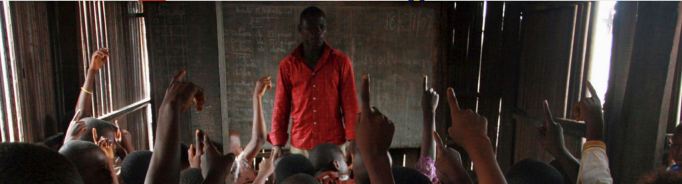

Learning in classroom best for early teens

Learning in language classes at school is an entirely different context. The normal pattern of these classes is to have one or more hourly lessons per week.

To succeed at learning with such little exposure to rich language input requires meta-cognitive skills that do not usually develop until early adolescence.

For this style of language learning, the later years of primary school is an ideal time to start, to maximise the balance between meta-cognitive skill development and the number of consecutive years of study available before the end of school.

Self-guided learning best for adults

There are, of course, some adults who decide to start to learn a second language on their own. They may buy a study book, sign up for an online course, purchase an app or join face-to-face or virtual conversation classes.

To succeed in this learning context requires a range of skills that are not usually developed until reaching adulthood, including the ability to remain self-motivated. Therefore, self-directed second language learning is more likely to be effective for adults than younger learners.

How we can apply this to education

What does this tell us about when we should start teaching second languages to children? In terms of the development of language proficiency, the message is fairly clear.

If we are able to provide lots of exposure to rich language use, early childhood is better. If the only opportunity for second language learning is through more traditional language classes, then late primary school is likely to be just as good as early childhood.

However, if language learning relies on being self-directed, it is more likely to be successful after the learner has reached adulthood.

Warren Midgley, Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics, University of Southern Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.