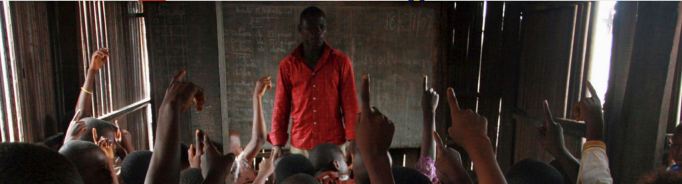

Timothy Vollmer, CC BY

Amy Thompson, University of South Florida

There are many benefits to knowing more than one language. For example, it has been shown that aging adults who speak more than one language have less likelihood of developing dementia.

Additionally, the bilingual brain becomes better at filtering out distractions, and learning multiple languages improves creativity. Evidence also shows that learning subsequent languages is easier than learning the first foreign language.

Unfortunately, not all American universities consider learning foreign languages a worthwhile investment.

Why is foreign language study important at the university level?

As an applied linguist, I study how learning multiple languages can have cognitive and emotional benefits. One of these benefits that’s not obvious is that language learning improves tolerance.

This happens in two important ways.

The first is that it opens people’s eyes to a way of doing things in a way that’s different from their own, which is called “cultural competence.”

The second is related to the comfort level of a person when dealing with unfamiliar situations, or “tolerance of ambiguity.”

Gaining cross-cultural understanding

Cultural competence is key to thriving in our increasingly globalized world. How specifically does language learning improve cultural competence? The answer can be illuminated by examining different types of intelligence.

Psychologist Robert Sternberg’s research on intelligence describes different types of intelligence and how they are related to adult language learning. What he refers to as “practical intelligence” is similar to social intelligence in that it helps individuals learn nonexplicit information from their environments, including meaningful gestures or other social cues.

COD Newsroom, CC BY

Language learning inevitably involves learning about different cultures. Students pick up clues about the culture both in language classes and through meaningful immersion experiences.

Researchers Hanh Thi Nguyen and Guy Kellogg have shown that when students learn another language, they develop new ways of understanding culture through analyzing cultural stereotypes. They explain that “learning a second language involves the acquisition not only of linguistic forms but also ways of thinking and behaving.”

With the help of an instructor, students can critically think about stereotypes of different cultures related to food, appearance and conversation styles.

Dealing with the unknown

The second way that adult language learning increases tolerance is related to the comfort level of a person when dealing with “tolerance of ambiguity.”

Someone with a high tolerance of ambiguity finds unfamiliar situations exciting, rather than frightening. My research on motivation, anxiety and beliefs indicates that language learning improves people’s tolerance of ambiguity, especially when more than one foreign language is involved.

It’s not difficult to see why this may be so. Conversations in a foreign language will inevitably involve unknown words. It wouldn’t be a successful conversation if one of the speakers constantly stopped to say, “Hang on – I don’t know that word. Let me look it up in the dictionary.” Those with a high tolerance of ambiguity would feel comfortable maintaining the conversation despite the unfamiliar words involved.

Applied linguists Jean-Marc Dewaele and Li Wei also study tolerance of ambiguity and have indicated that those with experience learning more than one foreign language in an instructed setting have more tolerance of ambiguity.

What changes with this understanding

A high tolerance of ambiguity brings many advantages. It helps students become less anxious in social interactions and in subsequent language learning experiences. Not surprisingly, the more experience a person has with language learning, the more comfortable the person gets with this ambiguity.

And that’s not all.

Individuals with higher levels of tolerance of ambiguity have also been found to be more entrepreneurial (i.e., are more optimistic, innovative and don’t mind taking risks).

In the current climate, universities are frequently being judged by the salaries of their graduates. Taking it one step further, based on the relationship of tolerance of ambiguity and entrepreneurial intention, increased tolerance of ambiguity could lead to higher salaries for graduates, which in turn, I believe, could help increase funding for those universities that require foreign language study.

Those who have devoted their lives to theorizing about and the teaching of languages would say, “It’s not about the money.” But perhaps it is.

Language learning in higher ed

Most American universities have a minimal language requirement that often varies depending on the student’s major. However, students can typically opt out of the requirement by taking a placement test or providing some other proof of competency.

sarspri, CC BY-NC

In contrast to this trend, Princeton recently announced that all students, regardless of their competency when entering the university, would be required to study an additional language.

I’d argue that more universities should follow Princeton’s lead, as language study at the university level could lead to an increased tolerance of the different cultural norms represented in American society, which is desperately needed in the current political climate with the wave of hate crimes sweeping university campuses nationwide.

Knowledge of different languages is crucial to becoming global citizens. As former Secretary of Education Arne Duncan noted,

“Our country needs to create a future in which all Americans understand that by speaking more than one language, they are enabling our country to compete successfully and work collaboratively with partners across the globe.”

![]() Considering the evidence that studying languages as adults increases tolerance in two important ways, the question shouldn’t be “Why should universities require foreign language study?” but rather “Why in the world wouldn’t they?”

Considering the evidence that studying languages as adults increases tolerance in two important ways, the question shouldn’t be “Why should universities require foreign language study?” but rather “Why in the world wouldn’t they?”

Amy Thompson, Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics, University of South Florida

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.